Hynobius dunni

Description:

Distribution and Habitat:

Keeping:

Diet:

This species, if kept in suitable conditions, proves to be extremely voracious, arriving to accept any prey of suitable size that is offered to it. The association between keeper and food also occurs rather easily, which is why feeding with the aid of tweezers is very easy. The diet is based on annelids and arthropods, therefore earthworms, frozen Chironomus, crickets, cockroaches and isopods can be offered in captivity. As always, the greater the variety of foods offered, the better the health of our animals will be. For adult/sub-adult animals, the preys must be administered 2 to 3 times a week, with a lesser frequency in the winter and a greater frequency in the reproductive and summer periods, while the juveniles must be fed more consistently.

Breeding:

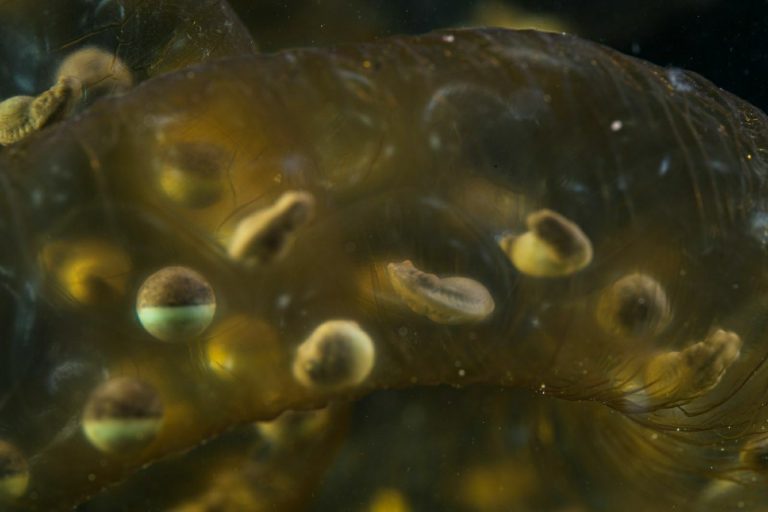

Mating can take place between early/mid December and late spring. The males, once entered the water, begin to compete for the sites (branches and other holds that will be supplied in abundant quantities) which they deem most suitable for the deposition of egg sacs by the females, from which they will be reached at a later time . Each female lays a single bifid sac measuring between 10 and 30 cm containing a variable number of eggs based on the age and state of health of the female (even more than 80 eggs per sac); these bags are normally fixed to submerged branches, more rarely to rocks and plant material. The males jealously protect the best branches, so to be the first to fertilize the sacs, fertilization which in this species is therefore external.

Egg Hatching:

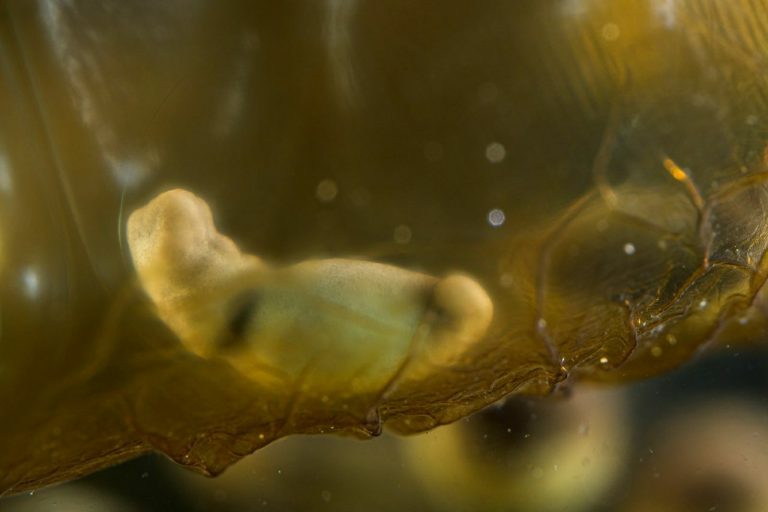

This perhaps represents the most complex passage as regards the reproduction of this species and probably that of all the Hynobiidae in general; the eggs, in fact, being in close contact with each other inside the bag, need to be regularly monitored and checked up, in order to avoid the onset of molds that could compromise the entire “brood”. First of all, it is advisable to remove the eggs from the tank or place of deposition, to avoid phenomena of cannibalism by the parents and other individuals present in the water. The sacs will be taken if possible without cutting the peduncle, completely or partially removing even the branch to which they are attached, and positioned as similar as possible to how they were oriented by the females inside containers between 5L and 20L. To combat the onset of mould, the use of very acidic water is recommended (you can proceed with an equal percentage of water from the deposition tank and new osmosis water, acidifying it by inserting catappa, oak, alder cones or coconut fiber). The insertion of an air stone or air filter for aquariums is recommended, in order to maintain minimal movement on the surface and prevent the water from stagnating. The sacs will be monitored periodically and, should mold develop on the eggs or certain embryos should stop developing, it will be advisable to make small incisions on them with the aid of a scalpel, and to remove with a syringe the compromise egg which could compromise the healthy embryos.

Growth and development of the Larvae:

Some of the larvae might need to help in getting out of the sacs, and once out, the larvae will feed on aquatic microorganisms, such as small crustaceans like Daphnia, Cyclops and nauplii of Artemia salina (well rinsed before being administered ) and other small freshwater invertebrates. Once these have reached 2-3 cm in length, they can also be fed with frozen food, such as Chironomus, and annelids of the right size, such as Enchytraeus and Lombriculus. It will gradually be necessary to separate the different larvae in different containers in relation to their size (the growth will not present the same rhythms for all), in order to avoid unpleasant episodes of cannibalism. When the larvae are close to metamorphosis (they will have all 4 limbs and will begin to reabsorb their gills) it will be advisable to lower the water level and place stones, trunks and outcropping/floating bark to facilitate their exit from the water.

The newly metamorphosed can be kept in a terrestrial environment, similar to that described for the adults, on a humid substrate (we recommend paper towels for the first few weeks in order to maintain a cleaner environment and to be able to verify that the animals defecate regularly) until reaching sexual maturity, which will occur on average between the third and fourth year of life. The juveniles will be fed with Chironomus and Enchytraeus, administered with tweezers, and/or with l1/l2 stages of crickets and cockroaches or with small isopods, coleoptera or diptera.

Ethological notes:

Availability:

Legislation:

About the Authors...

Jacopo Martino, born in Rome in 1997, graduating in biological sciences at “La Sapienza”University of Rome.

He worked for two years as a laboratory assistant for the zoology department of his university, then, he assisted and participated in various projects for the monitoring and study of herpetofauna, entomofauna and chiroptera. In 2022, is co-author of the paper “Sexual dichromatism and throat display in spectacled salamanders: a role in visual communication?”, later on, he participates in the publication of new works and scientific notes, in the herpetofaunistic, entomological, arachnological and ichthyological fields. Member of the Italian Gekko association (IGA), and administrator for projects and activities related to the world of amphibians for it. Member and social media manager for the Societas Herpetologica Italica (SHI). Member of the Italian Arachnology association (AIA) and special collaborator for the Arthropoda live Museum association. Founder and head of the research group of the ProgettoSeeds cultural association, which deals with naturalistic and environmental issues, within the Lazio region.

He has been keeping and breeding amphibians since 2014, with particular interest in the Ambystomatidae and Hynobidae families, and the Gymnophiona order.

Giuseppe Molinari, born in 1996 in Cesena, spent his childhood in the Tuscan-Romagna Apennines where he became passionate about naturalistic subjects.

He is currently graduating in Natural Sciences at the University of Bologna.

He is passionate about wildlife photography with a predilection for herpetofauna and he collaborates as a volunteer in various LIFE projects within the National Park of the Casentinesi Forests.

It has been breeding caudata continuously since 2014, in particular he focuses on species of Asian origin.